Illustrators go to war:

(#1) Hoover Memorial Exhibit Pavilion, Stanford, 4/5/17 – 9/2/17

(#1) Hoover Memorial Exhibit Pavilion, Stanford, 4/5/17 – 9/2/17

Visited on July 19th, with Juan Gomez. Extensive report follows.

The Hoover copy for the exhibit:

One hundred years ago [on 4/6/17] the United States — a young country with a small army — entered a global conflict the magnitude of which the world had never seen. Although President Woodrow Wilson assured the American population that “the war to end all wars” would be a victory for all mankind, many citizens failed to see the urgency in fighting a war abroad that was sure to be costly in terms of both money and lives.

Weapon on the Wall: American Posters of World War I marks America’s entry into the First World War by exploring one of the most powerful tools the country used to persuade its public to support and sustain the war effort: the poster. Drawing from the Hoover Institution’s world-renowned archive of more than 130,000 posters, the exhibition showcases the boldly graphic environment of 1917–18 and traces the pictorial treatment of the country’s most dire concerns, including enlistment, fear of the enemy, food conservation, morale on the home front, women in the workforce, and fund-raising for victory. Weapon on the Wall explores the lasting impact of poster images and slogans on American art and culture and also highlights the First World War as a landmark media war — an event that ushered in a new era of words as weapons and images as ideas.

Some background facts about the war, which lasted from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918 (July 28th is on my calendar as Sarajevo Day, remembering 1914, and Stonewall Day as well, remembering 1969; November 11th is Armistice Day, Veterans Day in the U.S.). From Wikipedia:

The trigger for the war was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, by Yugoslav nationalist Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914.

[The U.S. entered the war on 6 April 1917.]

… The United States had a small army, but, after the passage of the Selective Service Act, it drafted 2.8 million men, and, by summer 1918, was sending 10,000 fresh soldiers to France every day.

On to poster images from the show, which I’ll group into four big topical categories: recruitment, bonds, food, and women’s support. Some posters are keyed to the artist (JMF for James Montgomery Flagg, JCL for J. C. Leyendecker, HCC for Howard Chandler Christy); and three posters with notably phallic imagery are asterisked.

Recruitment. An all-purpose recruitment poster from JMF:

Three for the Navy.

(#3) *By HCC. Try not to think of Doctor Strangelove.

(#3) *By HCC. Try not to think of Doctor Strangelove.

Two for the Army.

For the Marines and the Tank Corps.

(#8) Gm. Teufel Hunden ‘Devil Dogs’

(#8) Gm. Teufel Hunden ‘Devil Dogs’

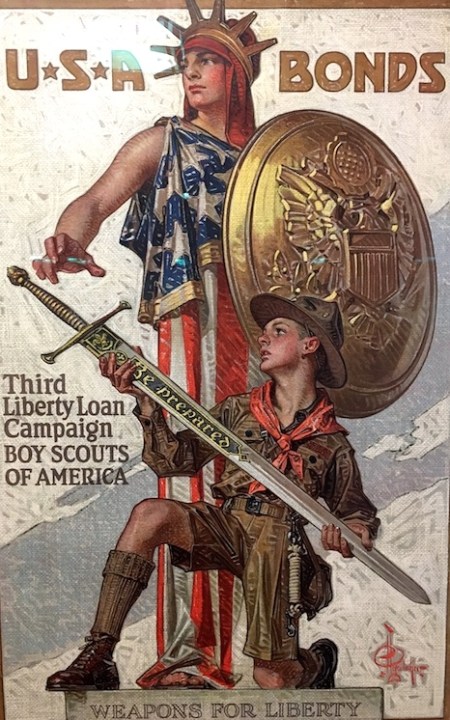

War bonds.

A number of posters were directed at foreign-born Americans; this one was aimed at any immigrants who came in through Ellis Island. Such posters were not, of course, designed for German Americans. Or for Irish Americans; 1916 saw the Easter Rising in Ireland, a rebellion against British rule, and the Irish were generally antagonistic towards Britain, so Irish Americans were viewed as potentially opposed to the war effort.

Food. Conserving it at home, growing your own, sending food to the men in the trenches. (There was a campaign specifically to send chocolate to fighting men — as well as one to send books to them.)

The zeugma here exploits an ambiguity in the transitive verb can; from NOAD2:

1 preserve (food) in a can. 2 North American informal dismiss (someone) from their job: he was canned because of a fight over promotion.

(#15) Poster in Yiddish to encourage food conservation

(#15) Poster in Yiddish to encourage food conservation

Aimed at Eastern European Jews in the U.S. Translation of the caption:

Food will win the war – You came here seeking freedom, now you must help to preserve it – Wheat is needed for the allies – waste nothing.

(#16) Uncle Sam leading women to preserve fruits and vegetables

(#16) Uncle Sam leading women to preserve fruits and vegetables

Women in the war effort. Not just enticing men to enlist and putting up food, but also providing a variety of` auxiliary services:

From Wikipedia:

The National League of Women’s Services (NLWS) was a United States civilian volunteer organisation formed in January 1917 to provide stateside war services such as feeding, caring for and transporting soldiers, veterans and war workers and was described as “America’s largest and most remarkable war emergency organization.”

… The League was divided into thirteen national divisions: Social and Welfare, Home Economics, Agricultural, Industrial, Medical and Nursing, Motor Driving, General Service, Health, Civics, Signalling, Map-reading, Wireless and Telegraphy, and Camping.

Three of the artists above were celebrated illustrators: JCL, JMF, and HCC (plus Normal Rockwell, who did war-support covers for the Saturday Evening Post).

J. C. Leyendecker (who’s responsible for two of the three asterisked posters above, #4 and #10) I’ve posted about on this blog. His specialty was commercial illustration, mostly for men’s fashion, and he produced many subtly or not-so-subtly homoerotic illustrations.

The other two were aggressively heterosexual, with a special eye for sexy women. And combat.

On James Montgomery Flagg, from Wikipedia:

James Montgomery Flagg (June 18, 1877 – May 27, 1960) was an American artist and illustrator. He worked in media ranging from fine art painting to cartooning, but is best remembered for his political posters.

… At his peak, Flagg was reported to have been the highest paid magazine illustrator in America. In 1946, Flagg published his autobiography, Roses and Buckshot. Apart from his work as an illustrator, Flagg painted portraits which reveal the influence of John Singer Sargent. Flagg’s sitters included Mark Twain and Ethel Barrymore; his portrait of Jack Dempsey now hangs in the Great Hall of the National Portrait Gallery. In 1948, he appeared in a Pabst Blue Ribbon magazine ad which featured the illustrator working at an easel in his New York studio with a young lady standing at his side and a tray with an open bottle of Pabst and two filled glasses sat before them.

Flagg’s great public creation was the now-standard image of Uncle Sam. From a 2/1/16 posting here “Only YOU”, quoting from Wikipedia:

Uncle Sam didn’t get a standard appearance until the well-known “recruitment” image of Uncle Sam was created by James Montgomery Flagg (inspired by a British recruitment poster showing Lord Kitchener in a similar pose). It was this image more than any other that set the appearance of Uncle Sam as the elderly man with white hair and a goatee wearing a white top hat with white stars on a blue band, a blue tail coat and red and white striped trousers.

The image of Uncle Sam was shown publicly for the first time, according to some, in a picture by Flagg on the cover of the magazine Leslie’s Weekly, on July 6, 1916, with the caption “What Are You Doing for Preparedness?” More than four million copies of this image were printed between 1917 and 1918.

Finally, Howard Chandler Christy (the artist of the asterisked #3). From Wikipeda:

Howard Chandler Christy (January 10, 1872 – March 3, 1952) was an American artist and illustrator, famous for the “Christy Girl” – a colorful and illustrious successor to the “Gibson Girl” – who became the most popular portrait painter of the Jazz Age era. Christy painted such luminaries as Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt, and Presidents Harding, Coolidge, Hoover, Roosevelt, and Truman. Other famous people include William Randolph Hearst, the Prince of Wales (Edward the VIII), Eddie Rickenbacker, Benito Mussolini, Prince Umberto, Amelia Earhart. From the 1920s until the 1940s, Christy was well known for capturing the likenesses of congressmen, senators, industrialists, movie stars, and socialites.

The Ambulance Corps. The Hoover Institution exhibit also included some cases of material about Stanford in World War I — about faculty and students who served in the Ambulance Corps before the U.S. entered the war and those who served (and often died) in the Armed Forces during the war.

From Wikipedia:

The American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps … was an organization started in London, England, in the fall of 1914 by Richard Norton, a noted archeologist and son of Harvard professor Charles Eliot Norton.

Its mission was to assist the movement of wounded Allied troops from the battlefields to hospitals in France during World War I. The Corps began with two cars and four drivers. The service was associated with the British Red Cross and St. John Ambulance.

Resistance to the war. Nothing in the Hoover exhibit would suggest the very extensive opposition to the war, in the U.S. and elsewhere. Summary from Wikipedia:

Opposition to World War I included socialist, anarchist, syndicalist, and Marxist groups on the left, as well as Christian pacifists, Canadian and Irish nationalists, women’s groups, intellectuals, and rural folk. Women across the spectrum were much less supportive than men.

The government’s response to this resistance was harsh, From “A ‘Resistance’ Stands Against [REDACTED]. But What Will It Stand For?” by Beverly Gage in the New York Times Magazine (in print on 2/5/17):

Some of the most significant shifts in modern American law and political culture came out of efforts birthed in panic and despair. During World War I, for instance, the United States banned criticism of the government, interned thousands of German Americans [foreshadowing the massive internment of Japanese Americans in World War II] and instituted widespread surveillance of immigrants and political radicals. Many Americans supported these policies; others feared that the country was abandoning cherished traditions of tolerance and free speech. In response, a small group of alarmed progressives founded an organization that came to be known as the American Civil Liberties Union. They lost many early courtroom battles, but their vision of a nation in which “civil liberties” were taken seriously eventually changed the face of American law and politics.

Leave a Reply