Yesterday, this startling ad from the Daily Jocks firm, specializing in premium men’s underwear from various companies — in this case, from the cheeky Australian company Supawear, offering its Fruitopia line in the color Watermelon:

Startling, because it shows a black man in a field of watermelon slices — an image that will evoke a racist stereotype, no matter what the intentions of the creators were.

[Added a bit later, with a note of mitigation. It turns out that not only Supawear but also the Daily Jocks company itself are Australian, and Australians can hardly be expected to appreciate the peculiarities of racial history in the U.S. (I’m not sure that Canadians will see the black + watermelon problem.) You might argue that a company that markets itself so heavily in the U.S. should be aware of sociocultural sore points, but frankly I think that’s asking a lot. So I suspect that Supawear and DJ have inadvertently fallen into a sinkhole, when they merely meant to be playful, colorful, and sexy.]

My main text here is a December 2014 piece in Atlantic magazine by William Black, “How Watermelons Became a Racist Trope: Before its subversion in the Jim Crow era, the fruit symbolized black self-sufficiency”. The full story is full of historical twists and turns, which Black’s account treats in detail, so it’s hard for me to avoid quoting most of it here. But I’ll put some material from 20th-century black culture, including black pushback against the stereotype, early in my discussion.

Background note. Put the watermelon slices to the side for a moment. #1 still shows a handsome, barely clad black man as an object of desire; is that racist? I don’t think so. Almost all the male models in ads for premium men’s underwear, regardless of race or ethnicity, are framed as objects of desire. It’s probably a good sign that so many black and (especially) hispanic/latino men are featured in these ads; this is a place where these men can get good work (so long as they have hot bodies, in one or another sense of hot).

Another background note. The name Fruitopia ostensibly “merely” refers to the fruit color of the garments; apparently Watermelon is the only fruit. But the fruit here probably also is functioning as an in-your-face use of a slur leveled at gay men.

Lead to the Atlantic piece.

It seems as if every few weeks there’s another watermelon controversy. The Boston Herald got in trouble for publishing a cartoon of the White House fence-jumper, having made his way into Obama’s bathroom, recommending watermelon-flavored toothpaste to the president. A high-school football coach in Charleston, South Carolina, was briefly fired for a bizarre post-game celebration ritual in which his team smashed a watermelon while making ape-like noises. While hosting the National Book Awards, author Daniel Handler (a.k.a. Lemony Snicket) joked about how his friend Jacqueline Woodson, who had won the young people’s literature award for her memoir Brown Girl Dreaming, was allergic to watermelon. And most recently, activists protesting the killing of Michael Brown were greeted with an ugly display while marching through Rosebud, Missouri, on their way from Ferguson to Jefferson City: malt liquor, fried chicken, a Confederate flag, and, of course, a watermelon.

While mainstream-media figures deride these instances of racism, or at least racial insensitivity, another conversation takes place on Twitter feeds and comment boards: What, many ask, does a watermelon have to do with race? What’s so offensive about liking watermelon? Don’t white people like watermelon too? Since these conversations tend to focus on the individual intent of the cartoonist, coach, or emcee, it’s all too easy to exculpate them from blame, since the racial meaning of the watermelon is so ambiguous.

But the stereotype that African Americans are excessively fond of watermelon emerged for a specific historical reason and served a specific political purpose. The trope came into full force when slaves won their emancipation during the Civil War.

Hold that emancipatory moment and skip ahead 50-70 years. There are now African-American communities in cities throughout the South, and they have their own customs, one of which is street vendors selling food — not vendors fixed in place, like modern food stands and food trucks on the street, but vendors moving through the streets (on foot, usually with a wagon, but otherwise like modern ice-cream trucks), where they can be haled by people who want to buy their wares. (Such vendors used to be common in all sorts of working-class communities, not just African-American ones.)

African-American street vendors are well represented in the great American folk opera Porgy and Bess (set in Catfish Row, a fictional African-American community based on a neighborhood of Charleston SC, and first performed in 1935), in the “Vendor’s Trio”, with the calls of vendors selling strawberries, honey, and crabs. I’ll get back to P&B later, for several reasons, including the personal one that I haven’t been able to get the strawberry woman’s call out of my head since I first heard it, oh, maybe 60 years ago. You can watch the strawberry woman’s call here, in what I believe to be a clip from the 1959 movie of P&B, with Lynne Thigpen portraying the strawberry woman.

Stay with me here. We now move from the African-American communities of the South to their transplanted versions in the North, after the Great Migration. Customs and practices travelled with the people — which brings us to the African-American communities of Chicago, where Herbie Hancock found inspiration for his jazz standard “Watermelon Man” (first released in 1962); the watermelon man was among the street vendors of Hancock’s youth. From Wikipedia:

“Watermelon Man” is a jazz standard written by Herbie Hancock, first released on his debut album, Takin’ Off (1962).

[Its first] version was released as a grooving hard bop and featured improvisations by Freddie Hubbard and Dexter Gordon. A single of the tune reached the Top 100 of the pop charts. Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaría released the tune as a Latin pop single the next year on Battle Records, where it became a surprise hit, reaching #10 on the pop charts. Santamaría’s recording was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1998. Hancock radically re-worked the tune, combining elements of funk, for the album Head Hunters (1973).

… The form is a sixteen bar blues. Recalling the piece, Hancock said, “I remember the cry of the watermelon man making the rounds through the back streets and alleys of Chicago. The wheels of his wagon beat out the rhythm on the cobblestones.” The tune, based on a bluesy piano riff, drew on elements of R&B, soul jazz and bebop, all combined into a pop hook. Hancock joined bassist Butch Warren and drummer Billy Higgins in the rhythm section, with Freddie Hubbard on trumpet and Dexter Gordon on tenor saxophone. Hancock’s chordal work draws from the gospel tradition, while he builds his solo on repeated riffs and trilled figures.

… The tune is a jazz standard and has been recorded over two hundred times.

There’s a stunning 1991 performance by Hancock and Miles Davis that you can watch here.

Now, Hancock was surely aware of the racist history of watermelons, but what this piece primarily represents is his affectionate memory of the street life of his childhood, in a place where if you were in your neighborhood, you were free to enjoy watermelon simply as home food (even if you wouldn’t eat it within the gaze of whites — though of course there’s the option of being in-your-face uppity and flaunting your watermelon). But then the song can also be seen as an anthem to that neighborhood and its people, and a pushback against racist attitudes.

Now back to the Atlantic article, suspended at the Emancipation Proclamation, after which I’ll move to the 1970 movie Watermelon Man, definitely in-your-face. And after that, back to Porgy and Bess and the racial storms that have swirled around it for 80 years.

Free black people grew, ate, and sold watermelons, and in doing so made the fruit a symbol of their freedom. Southern whites, threatened by blacks’ newfound freedom, responded by making the fruit a symbol of black people’s perceived uncleanliness, laziness, childishness, and unwanted public presence. This racist trope then exploded in American popular culture, becoming so pervasive that its historical origin became obscure. Few Americans in 1900 would’ve guessed the stereotype was less than half a century old.

… [Watermelon tropes from the British Empire] made their way to America, but the watermelon did not yet have a racial meaning. Americans were just as likely to associate the watermelon with white Kentucky hillbillies or New Hampshire yokels as with black South Carolina slaves.

This may be surprising given how prominent watermelons were in enslaved African Americans’ lives. Slave owners often let their slaves grow and sell their own watermelons, or even let them take a day off during the summer to eat the first watermelon harvest. The slave Israel Campbell would slip a watermelon into the bottom of his cotton basket when he fell short of his daily quota, and then retrieve the melon at the end of the day and eat it. Campbell taught the trick to another slave who was often whipped for not reaching his quota, and soon the trick was widespread. When the year’s cotton fell a few bales short of what the master had figured, it simply remained “a mystery.”

But Southern whites saw their slaves’ enjoyment of watermelon as a sign of their own supposed benevolence. Slaves were usually careful to enjoy watermelon according to the code of behavior established by whites. When an Alabama overseer cut open watermelons for the slaves under his watch, he expected the children to run to get their slice. One boy, Henry Barnes, refused to run, and once he did get his piece he would run off to the slave quarters to eat out of the white people’s sight. His mother would then whip him, he remembered, “fo’ being so stubborn.” The whites wanted Barnes to play the part of the watermelon-craving, juice-dribbling pickaninny. His refusal undermined the tenuous relationship between master and slave.

Emancipation, of course, destroyed that relationship. Black people grew, ate, and sold watermelons during slavery, but now when they did so it was a threat to the racial order. To whites, it seemed now as if blacks were flaunting their newfound freedom, living off their own land, selling watermelons in the market, and — worst of all — enjoying watermelon together in the public square. One white family in Houston was devastated when their nanny Clara left their household shortly after her emancipation in 1865. Henry Evans, a young white boy to whom Clara had likely been a second mother, cried for days after she left. But when he bumped into her on the street one day, he rejected her attempt to make peace. When Clara offered him some watermelon, Henry told her that “he would not eat what free negroes ate.”

Newspapers amplified this association between the watermelon and the free black person. In 1869, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper published perhaps the first caricature of blacks reveling in watermelon. The adjoining article explained, “The Southern negro in no particular more palpably exhibits his epicurean tastes than in his excessive fondness for watermelons. The juvenile freedman is especially intense in his partiality for that refreshing fruit.”

… The primary message of the watermelon stereotype was that black people were not ready for freedom. During the 1880 election season, Democrats accused the South Carolina state legislature, which had been majority-black during Reconstruction, of having wasted taxpayers’ money on watermelons for their own refreshment; this fiction even found its way into history textbooks. D. W. Griffith’s white-supremacist epic film The Birth of a Nation, released in 1915, included a watermelon feast in its depiction of emancipation, as corrupt northern whites encouraged the former slaves to stop working and enjoy some watermelon instead. In these racist fictions, blacks were no more deserving of freedom than were children.

[As mass-produced pianos and sheet music became popular in the late nineteenth century, so did “coon songs,” popular tunes that mocked African Americans for their lazy, shiftless, childish ways.]

It may seem silly to attribute so much meaning to a fruit. And the truth is that there is nothing inherently racist about watermelons. But cultural symbols have the power to shape how we see our world and the people in it, such as when police officer Darren Wilson saw Michael Brown as a superhuman “demon.” These symbols have roots in real historical struggles — specifically, in the case of the watermelon, white people’s fear of the emancipated black body. Whites used the stereotype to denigrate black people — to take something they were using to further their own freedom, and make it an object of ridicule. It ultimately does not matter if someone means to offend when they tap into the racist watermelon stereotype, because the stereotype has a life of its own.

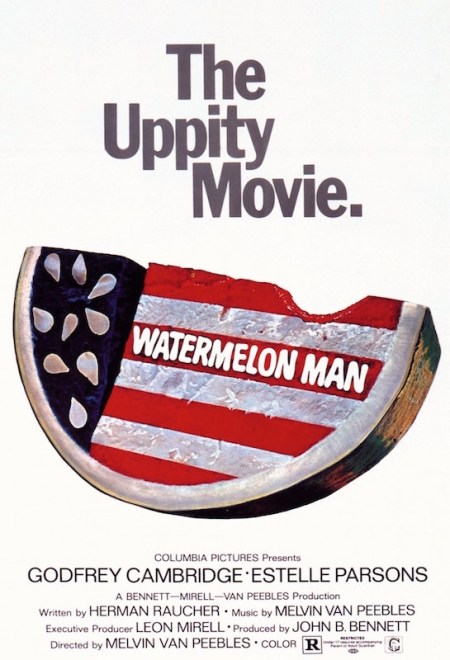

The 1970 film.

From Wikipedia:

Watermelon Man is a 1970 American comedy-drama film, directed by Melvin Van Peebles. Written by Herman Raucher, it tells the story of an extremely bigoted 1960s era White insurance salesman named Jeff Gerber, who wakes up one morning to find that he has become Black. The premise for the film was inspired by Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and by John Howard Griffin’s autobiographical Black Like Me.

Van Peebles’ only studio film, Watermelon Man was a financial success, but Van Peebles did not accept Columbia Pictures’ three-picture contract, instead developing the independent film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. The music for Watermelon Man, written and performed by Van Peebles, was released on a soundtrack album.

Hancock’s “Watermelon Man” plays no part in the movie.

Defiant, but with the edge taken off some by comedy. So the movie fits into a body of work by black actors and comedians that is defiant, sometimes aggressively so, on matters of race.

Porgy and Bess. Back to the 1930s. From Wikipedia:

Porgy and Bess is an English-language opera composed in 1934 by George Gershwin, with a libretto written by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin from Heyward’s novel Porgy and later play of the same title. Porgy and Bess was first performed in New York City on September 30, 1935, and featured an entire cast of classically trained African-American singers — a daring artistic choice at the time. After suffering from an initially unpopular public reception due in part to its racially charged theme, the Houston Grand Opera production of the opera in 1976 gained it new popularity, eventually becoming one of the best-known and most frequently performed operas.

Racial controversy: From the outset, the opera’s depiction of African Americans attracted controversy. Problems with the racial aspects of the opera continue to this day. Virgil Thomson, a white American composer, stated that “Folklore subjects recounted by an outsider are only valid as long as the folk in question is unable to speak for itself, which is certainly not true of the American Negro in 1935.” Duke Ellington stated “the times are here to debunk Gershwin’s lampblack Negroisms.” (Ellington’s response to the 1952 Breen revival was, however, almost completely the opposite. His telegram to the producer read: “Your Porgy and Bess the superbest, singing the gonest, acting the craziest, Gershwin the greatest.”) Several of the members of the original cast later stated that they, too, had concerns that their characters might play into a stereotype that African Americans lived in poverty, took drugs and solved their problems with their fists.

All sorts of racial issues here. Beyond the ones above: black performers on stage, in any sort of a performance, were a problem for many white audiences, because the audience was below the level of the performers; the performers were physically superior to their audience. And P&B showed a black couple in a romantic relationship, a representation that made many white audiences uncomfortable back in 1935 — and up through the days of radio and television (where black couples in love and physically demonstrative with one another were very long in coming).

Then there was the language. Here’s a quotation from an appreciative piece by Joe Nocera in the NYT in 2012 (on the occasion of a new Broadway production of P&B), as quoted in a posting of mine from 1/25/12, “A word now shunned”:

When George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” — arguably the most important piece of American music written in the 20th century — first opened on Broadway in 1935, the opera’s libretto was littered with a word now shunned as an antiblack slur. The African-American residents of Catfish Row, the only slightly imaginary block in Charleston, S.C., where the opera is set, used it liberally, and so of course did the white characters during their occasional menacing visits.

Note the dual use of nigger in P&B: as a racial identifier used by black people among themselves (a usage amply exemplified in some of Richard Pryor’s stand-up routines from the 1970s and 1980s, but one that he later regretted using, at least “in public” like this), and as a slur and a threat used by whites to blacks. And note the topic of my 2012 posting, the almost comic lengths Nocera was obliged to go to by the NYT if he was going to address the question of how the word nigger is used in P&B. The paper absolutely forbids the use of the word in its pages, even in quotations (the position is that the word is so toxic that it cannot ever be uttered, for any purpose), and it tries to forbid all ostentatious avoidance strategies (like asterisking or locutions like the N-word), strategies that would easily allow a reader to identify the specific locution in question. This obliges its writers to adopt extraordinarily indirect devices for referring to the word, even when the word is itself the topic of the story — like Nocera’s sniffy eight-word phrase “a word now shunned as an antiblack slur”.

Leave a Reply