In the January/February issue of Stanford magazine, “Watch Your Words, Professor: In 1900, Jane Stanford forced out a respected faculty member. Was he a martyr to academic freedom or a racist gadfly who deserved what he got?” by Brian Eule, beginning:

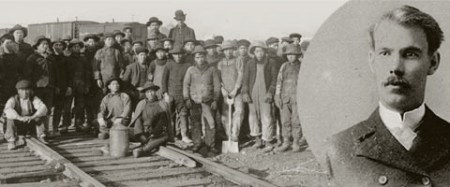

On a Tuesday afternoon in November 1900, Edward Alsworth Ross gathered several student reporters in his campus office. Ross, 33 years old and a Stanford economics professor of seven years, had joined the university just two years after its opening. He was a captivating sight, 6-foot-5 and nattily dressed in a suit that favored his athletic physique.

Ross was popular with students and esteemed in his field. David Starr Jordan, the university’s first president, had recruited him not once but twice. Plucked from Jordan’s former home at Cornell, Ross was emerging as a scholarly star. Now, his time at Stanford was coming to an abrupt end.

Ross held a lengthy written statement he had prepared for the San Francisco newspapers. He handed it to the students.

“Well, boys,” he said, “I’m fired.”

The story continues:

One hundred and fifteen years later, the reasons for Ross’s departure remain in dispute. The matter was precipitated by a series of public pronouncements Ross had made on political matters between 1896 and 1900, a practice that put him at odds with university co-founder Jane Stanford. Was he forced out because of his outspoken opinions or because he broke rules prohibiting partisan advocacy? What is not in dispute is that Mrs. Stanford insisted that Ross be sacked despite the vigorous objections of Jordan, who finally relented.

Ross’s dismissal drove a wedge between Stanford faculty and the administration and resulted in a spate of resignations by other professors. More broadly, it galvanized efforts to codify protection of academic freedom and indirectly led to the establishment of tenure. As it turned out, that hastily arranged press conference in Ross’s office was a seminal moment in the history of higher education.

Ross’s outspoken opinions came in two areas: his passionate support for the Free Silver movement, and his equally passionate opposition to the immigration of Chinese. From Ross:

“I took the ground that the high standard of living that restrains multiplication in America will be imperiled if Orientals are allowed to pour into this country in great numbers before they have raised their standards of living and lowered their birth rate.”

And then the consequences:

In the years after Ross’s dismissal, [philosophy professor Arthur] Lovejoy — one of the professors who had resigned from Stanford and ultimately went to Johns Hopkins University — teamed with John Dewey of Columbia University to establish an organization aimed at ensuring academic freedom for faculty. In 1915 the newly formed American Association of University Professors released its “Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure.” Among other things, the declaration noted: “Official action relating to reappointments and refusals of reappointment should be taken only with the advice and consent of some board or committee representative of the faculty.”

(John Dewey is the famous philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer. Arthur Lovejoy is the distinguished philosopher and historian of ideas, author of the excellent The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea.)

Ross and the Chinese menace:

Ross went on to a successful career at Nebraska and then Wisconsin.

Leave a Reply