Metatext in the comics

Arnold M. Zwicky, Stanford University SemFest 15 (2014)

[This material appears in two forms: a handout at the SemFest, reproduced (without division into pages) here, and a posting of 2/12/14 on my blog (which has the cartoons only through links).]

Cartoons and comics have main content – visuals, usually (though not always) with speech from the characters. But there often is other material designed to frame the way to read this text: metatext, of at least six types.

1. Inserts. These are bits of text within the body of a panel or panels, but not attributed to any of the characters. Often they are crucial to understanding what’s going on – indicating changes in place (“meanwhile, back in Metropolis”) or time (“three days later”), but sometimes providing a narrative background without which the comic would be incomprehensible (Zippy the Pinhead frequently has inserts of this sort – in which case they should be thought of as a third kind of main content.

A time insert from xkcd:

This cartoon is discussed in my posting “Messing with my mind” of 2/11/14.

Here’s a Zippy that advances the story almost entirely through extended inserted text, discussed in my posting “Fun is bowling” of 1/28/14):

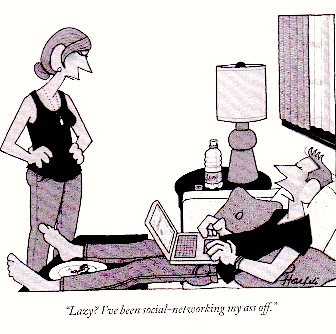

2. Captions and 3. Titles. Captions (located below the body of the comic) are so common in single- panel cartoons that they’re scarcely worth commenting on, except to note that single-panels are often so poor in context and content that captions are valuable for the reader. (Single-panel cartoons often have captions, inside quotation marks, instead of speech balloons, showing what a character is saying. In particular, this is New Yorker style. Not really metatext, but a piece of text that happens to be located outside the main image.)

A New Yorker example, from William Haefeli:

Non-speech captions are often dispensable, but nevertheless useful, and they can provide a “second smile” (thanks to Michael Siemon for this felicitous term) for the reader (visual: man waiting at airport with a sign “Godot”; funny as it stands, but the caption “Another day at Beckett International Airport” provides a second smile):

(Discussion on my blog,in “Caption exercise” of 2/20/14. )

Sometimes the caption is essential, as here:

(Discussion in “Indirect pun” on my blog in 4/20/13 .) Without the caption the strip is inscrutable.

As for titles, in principle, titles (located above the body of the comic or at the left side) serve to announce the topics of comics, especially three- or four-panel strips. Here’s a framing title from Rhymes With Orange:

(Discussed in my posting “Swamp Thing” of 3/1/14.) You can get the pun without the title, but you might well not recognize the drinker as the character Swamp Thing.

Strip #1 above (xkcd) has an informative title (beginning with “My hobby”) as well as an insert.

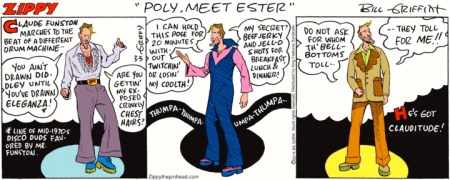

But titles have other uses. A great many Zippys have titles, but these are rarely just helpful topic declarations; instead, they are additional jokes, beyond the ones in the body of the comic, providing second smiles, as in this example, from my posting “Eleganza” of 3/5/14:

The title here has a play on polyester.

4. Accompanying text and 5. Mouseovers. These are “add-ons”, outside the body of the strip.

Accompanying text is available on the net and, in principle, with print comics, but mostly used on the net, where explanation or snarky commentary can be provided after the comic itself. Scenes From a Multiverse and Dinosaur Comics regularly have accompanying text. In principle, this text could illuminate the strip, but more often than not it’s about the cartoonist’s life. So from Jon Rosenbaum on his Scenes From a Multiverse entitled “Skyball part 5! (8/7/13): (http://amultiverse.com/comic/2013/08/07/skyball-part-5/):

This is SFAM #500! Whee!

I’m previewing the Goats Mini I’m working on for the Goats IV Kickstarter rewards for the next few days. Here’s part 5. Enjoy the sneak peek!

(followed by a bunch of tweets). Discussion of the strip in my posting “Bilingual wordplay” of the same day.

Mouseovers are available only on the net. These framing or commenting messages appear when a mouse hovers over the image. xkcd is especially given to mouseovers. Often they provide second smiles, as in strip #1 (xkcd), which has not only an insert and a title, but also this mouseover:

Like spelling “dammit” correctly – with two m’s – it’s a troll that works best on the most literate.

which is only tangentially related to the main content of the strip.

6. Footnotes. Occasionally, comics have expressions marked as footnotes (with the standard asterisk), with the explanatory footnote itself (again, marked with an asterisk) appearing somewhere inside or close to the body of the comic.

7. Summary. Comics regularly have material in addition to images and represented speech (in speech balloons or their equivalent — lines from speakers to represented speech — or in speech captions). Much of the time, this material enriches, sometimes crucially, the semantic/pragmatic content of the comic. Other times it presents an extra stream of content, only loosely related to the main content of the strip.

December 23, 2014 at 5:55 am |

The actual handout was formatted in MS Word. It’s taken quite some time to create an html version.

December 29, 2014 at 4:33 am |

xkcd is not simply given to mouseovers; they are a regular feature of every strip since #1.

As usual, there is a TVTropes page about this.